THE ART & DISCIPLINE OF USING 'PSQ7R' TO ACCELERATE YOUR READING

Firstly, let me introduce you to ‘PSQ7R’:

This is essentially my personal variation of the original ‘SQ3R’developed by Francis Robinson, a teacher/psychologist of Ohio State University in the 1940s.

P = PURPOSE

Firstly, just before you start to read any new text materials, you need to define your purpose.

In other words, you have to ask yourself mentally the following questions:

- what is the purpose of your reading or why are you reading this chapter or this lesson or this textbook or what is your end goal?...or what are you expected to remember?;

- how important will be the reading materials for you?

- Do you want a global overview or detailed information?

- how much time are you prepared to invest in your reading?

Examples of end goals:

- for a test/exam;

- for a class or group discussion;

- for a short presentation to a group;

- for pleasure or the fun of it;

- for a project assignment or report;

- for general ideas only;

All these reading objectives will eventually influence and ultimately determine your reading method, entry point, depth of navigation and reading speed.

For example, if you are just reading for general ideas only, then you don’t have to read the whole book but skim and/or scan through the book to get what you need.

But, if you are reading for a test or exam, it is a different ball game, as you need to read the book or each chapter or lesson slowly and carefully.

S = SURVEY

Upon defining your purpose, the next thing you need to do just before you commence to read a new chapter or lesson, is do a quick survey of the contents within, as follows:

- Read the chapter or lesson objectives, if any;

- Read the introduction;

- Read the opening paragraph, if any;

- Scan the headings and subheadings;

- Look at the illustrations, pictures, diagrams, graphs, tables, captions, etc.., if any;

- Pay attention to any words or phrases in Bold Print or italics;

- Read any text captured in boxed sections;

- Read any marginal notes (usually alongside selected paragraphs), if any;

- Read the ending paragraph and/or concluding summary, if any;

- Read the chapter or review questions at the end of the chapter or lesson, if any;

If it is a new textbook, do a quick survey of the following additional areas, prior to the above:

- Scan the front, inside, and back covers, especially the credit reviews by others;

- Read the biography of the author;

- Read the Preface;

- Read the Table of Contents;

- Read the Concluding Chapter at the end of the book, if any;

- Browse the Glossary or Appendix at the end of the book, if any;

- Browse the Bibliography at the end of the book, if any;

- Browse the Index at the end of the book, if any;

The purpose of this quick survey is to generate a global overview or big picture of the chapter or lesson or the book. It will definitely give you a rough sense of the overall structure, organisation or plan of the chapter or lesson or book.

With a quick survey, you will find that details in the text are much more easily remembered because of their relationship to the big picture.

In military jargon, we call this quick survey a reconnaissance (recon) patrol to map out the enemy terrain, to identify enemy targets for hits, to flush out enemy hideouts, to locate the safest attack route, and also fastest escape route.

More importantly, this quick survey helps you to build a familiar background and activate your prior knowledge to determine what you know and what you don’t know and also what you want to know

Normally, a quick survey will take only a few minutes, but it is time well spent.

Q = QUESTION

From your earlier quick survey, you have already scanned the headings and subheadings in your chapter or lesson or text book.

Take these headings and subheadings and convert all of them into questions, one by one. By formulating questions in this manner, you are learning to put your mind into a questioning mode. They keep you mentally alert.

Think about it. I am sure you know the graphic symbol for question is "?".

If you turn it around, it looks like a hook do you agree?

Questions serve as memory hooks!

To put it in perspective, reading is fishing for information - and ultimately, ideas.

Next, also from your quick survey, you have already read the chapter or review questions at the end of the chapter or lesson.

Indirectly, these questions are actually telling you what the important points of the chapter or lesson will be.

These questions therefore serve as your reference points as you proceed to read the chapter or lesson also as your memory hooks!

By consciously applying a series of questions to whatever you read, you are actually developing your ability to think critically in your reading.

I always tell my students that reading is a thinking process, not a regurgitating process!

One of the best ways to formulate your questions is to use what I call the '6W3H Questioning Process’ (this is my personal modification of the conventional ‘Journalists Questions’), as follows:

- What?

- Who?

- Where?

- When?

- Which?

- Why?

- How?

- How much or many?

- How frequent?

Now, you are putting yourself on the mark and ready to go.

(At this juncture, I would like to recommend Adam Robinson’s ‘What Smart Students Knows’. This wonderful author has very skillfully crafted a series of additional powerful questions to help readers develop an effective questioning mind, as follows:

- BEFORE YOUR READING(Pre-Reading Questions);

- WHILE YOU ARE READING (Reading-in-Progress Questions; and

- AFTER YOUR READING (Post-Reading Questions);

Please get hold of this book.)

R (1) = READ QUICKLY & SELECTIVELY

This is the quick and selective reading part of the entire process.

In a way, you are reading quickly and selectively to find all the answers to all your questions (in your quick survey).

Learn to read quickly by using your index finger as a pacer as your read.

Move your pacer i.e. your index finger, and glide it horizontally across the width of the paragraph, from left to right, just along the lower portion of each sentence as you read it.

When your pacer reaches the end of the sentence, move it quickly to the front of the next sentence below, and continue the motion as if you are continuously writing a "Z" with your pacer.

First, you can start by gliding it slowly as you read, and then pick up your speed as you feel comfortable reading faster.

The purpose of the pacer is to "guide" your eye balls in a steady manner.

Let me explain.

Our eye balls are hard-wired to move rapidly and naturally. In science, we call them saccadic movements. This has to do with our evolutionary design. Our forefathers were hunters-gatherers our eye balls were already trained to scan the environment at far and open distances... to look out for animals to hunt, and at the same time, to watch out for predators!

So, when we read, which is at close range, we need to keep our eyes under control and guide them to read the small text in a steady manner.

Once you have all the questions formulated from the headings and subheadings, and also the review questions from the end of the chapter or lesson at the back of your mind, you can begin to read quickly.

At this juncture, I want to introduce you how to identify or recognise the many text organizational patterns often used by authors in writing academic materials:

Firstly, learn to recognise "signal words".

"Signal words" tell you what is coming up as you read, and what to watch for as well as what you already have read.

Watching out "signal words" as you read will immediately help to focus your attention or signal you to make note of the information to follow.

Listed below are some common signal words and their meanings:

An addition to original train of thought:

Also;

in addition

further;

furthermore;

lastly;

moreover;

first;

second;

secondly;

too;

author is changing, challenging or contradicting original train of thought:

although;

after all;

but;

by contrast;

however;

nevertheless;

on the contrary;

yet;

still;

despite the fact;

author is defining:

referred to as;

is;

the same as;

means;

termed;

defined as;

means the same;

a synonym for;

author is pointing out similarities/differences:

alike;

similarly;

likewise;

by the same token;

in the same vein;

unlike;

otherwise;

different;

contrasts with;

on the other hand;

opposite;

as opposed to;

author is introducing examples and illustrations:

for example;

for instance;

specifically;

in other words;

i.e.;

author is introducing some causes/effects:

it is because;

because;

due to;

results in;

unless;

effect;

cause;

the quality;

attribute;

for this reason;

if;

as a result;

stems from;

consequently;

thus;

therefore;

hence;

in response;

author is helping readers to follow a sequence in time:

in the meantime;

next;

soon;

after a while;

in time;

of late;

thereafter;

afterwards;

finally;

author is repeating a point already made:

in short;

in brief;

in conclusion;

in other words;

on the whole;

in summary;

to reiterate;

to sum up;

Once you recognise and understand these "signal words", you will begin to understand how the text in each paragraph is organised. This is the basis of the second text reading technique, which I will illustrate under R(2) as follows.

R(2) = RE-READ SLOWLY

This is the careful and deliberate reading part of the entire process.

As you begin to re-read and see a lot of those "signal words" listed under CAUSE/EFFECT in a given paragraph, you will begin to understand that the paragraph is organised in a CAUSE/EFFECT pattern.

All you need to do next is to re-read slowly to gather the relevant information pertaining to the CAUSE or CAUSES and EFFECT or EFFECTS in the given paragraph.

Likewise, when you see a lot of those "signal words" listed under COMPARISON/CONTRAST in a given paragraph, then you will begin to understand that the paragraph is organised in a COMPARISON/CONTRAST pattern.

All you need to do next is to re-read slowly to gather the relevant information pertaining to similarities and differences in the given paragraph.

In a nut shell, I call these text organisational or writing patterns.

Research indicates that readers who can recognise and identify the most common organisational patterns of textbook writing can comprehend the material faster and can also recall the information better. The performance of these readers on summarising and other comprehension tasks is superior to that of readers who are not knowledgeable about text structure.

Other research shows that learning to recognise organisational patterns increases your understanding of key ideas.

The following are some of the most common organisational patterns:

- simple listing;

- order/sequence;

- comparison/.contrast;

- cause/effect;

- problem/solution;

- classification;

- definition;

- example;

- mixed patterns (a combination of two or more patterns);

All of the patterns are found in all academic disciplines.

For a broader and deeper understanding of "signal words" and text organisational patterns, with hands-on application exercises, I strongly recommend you to read:

1. 'Steps to Reading Proficiency', by Anne Dye Phillips & Peter Sotiriou;

2. 'Power Reading Efficient Learning', by Eleanor

Now, let us move to the next R.

R(3) = REDUCE INFORMATION TO KEY IDEAS;

I always tell my students that the purpose of reading, irrespective of the text content, is to gather information and "fish out" the key ideas.

Key ideas help you to recognise and remember supporting information. They are the topics of entire paragraphs or lessons. Key ideas are often found in the first or last sentences /paragraphs, but they can be located anywhere within the text material.

Here are some basic guidelines for identifying key ideas:

- use the headings and/or subheadings in the text;

- ask questions: what is this paragraph all about? What does the author assert or want me to understand about this topic?;

- List details and ask: what do these details have in common?;

- Look for general statements: underline the most general statement and ask: which statement best represent the key idea of the paragraph?;

- State the key idea as a complete sentence;

For additional strategies to reduce information to key ideas, and more precisely, to gather information, please refer to my SEVEN PERSPECTIVES OF INFORMATION GATHERING AT HIGH SPEEDS.

R(4) = RECORD KEY IDEAS;

This is the note-taking and note-making part of the entire process.

There are many effective ways to record key ideas...to be more precise, to take notes and make notes.

You can use outlining and/or mapping formats for your note-taking and note-making.

Please refer to my SEVEN PERSPECTIVES OF INFORMATION GATHERING AT HIGH SPEEDS.

R(5) = RECITE;

It is a useful exercise to stop regularly to silently recite to yourself what you have just recorded as key ideas, without looking at your textbook or notes. Be sure to put ideas in your own words, as this will improve your ability to retain the material. Answer questions aloud and listen to your responses to see if they are complete and correct. If they are not correct, re-read the material and answer the question again. This form of rehearsal increases the likelihood that you will retain the material.

R(6) = REFLECT;

Research indicates that comprehension and retention of information are increased when you elaborate new information. This is to reflect on it, to turn it this way and that, to compare and make categories, to relate one part with another, to connect it with your other knowledge and personal experience, and in general to organise and reorganise it. This may be done in your minds eye, and sometimes on paper.

You can reflect on the text you have just read or learnt by asking.

- What is the significance of these facts or ideas?

- On what principle are they based;

- To what else could they be applied?

- How do they fit in with what I already know?

- What can I see that lies beyond these facts and ideas?

R(7) = REVIEW;

Reviewing is the key to figuring what you have just learnt and what you need to remember. The best times to review are right after reading while the material is still fresh on your mind.

I would suggest that for every 20-30 minutes of reading/learning, you need to spend 5-10 minutes reviewing what you have just read/learnt.

After this immediate review, you need to review your learnt materials periodically and systematically as follows:

- every 7 days;

- every 30 days;

- every 90 days;

- every 180 days;

I call this exercise Spaced Repetition, which is a very powerful memory enhancement tool.

Another important point to remember:

you need to review your lesson or lecture within 24 hours after class, otherwise 80% is lost;

SEVEN PERSPECTIVES OF INFORMATION GATHERING AT HIGH SPEEDS!

1. Highlighting & Underlining;

As you proceed along through a reading, you may have developed strategies to identify, mark and summarise information you find of importance. The most popular way of identifying or marking key information is to highlight the text and/or underline passages so that you can return to them later. In general, the process of marking the text so that you can return to important information is a very important one.

Here are some effective highlighting tips:

Do highlight:

- Keywords;

- Key phrases;

- Key ideas;

- Supporting details;

- Terms, definitions & equations;

- Answers that correspond to your questions;

- Key word items in a list;

- Formulas, principles, rules;

Avoid highlighting:

- whole pages;

- whole paragraphs;

- whole sentences;

- bold-faced headings;

- bullets or numbers without key words when you have no corresponding questions;

- math problems;

The following 12 guidelines will help you master the skill of effective underlining:

- use a pencil;

- develop some system to distinguish key ideas and other important ideas;

- before you begin to underline a chapter, assess your prior knowledge;

- before you begin to underline, survey the chapter;

- read a section or paragraph first, and then underline;

- use your knowledge of text organisational patterns to help you underline effectively;

- observe headings and subheadings to help you determine what to underline;

- underline in telegraphic terms;

- underline no more than about 15 to 20% of the page;

- if you have trouble determining what supporting ideas are important, first read the key idea; then look for support or evidence for the key idea;

- Look for numbers or bullets that are often used to mark important concepts that are in stages or in a list;

- Make sure you do not underline in such a way that you change the meaning of the paragraph;

2. Marginal Notations;

These refer to all of the pencil marks used to call attention to terms and main points and to the remarks written in the margins.

The following types of marginal notations are helpful:

- draw two parallel vertical lines in the margin, next to the paragraph, to mark location of main ideas and/or summary statements;

- circle unknown words;

- put question mark (?) in the margin, next to paragraph you don’t quite understand & for which you need further clarification;

- Defn. to mark an important definition of a word you have marked in the text;

- Ex. To mark an example of a difficult concept;

- Parentheses {} around an example or anything you want to find if you need it;

- Numbers for important lists of people, theories, reasons, historical events;

- Some type of mark (for example, an asterisk *) for an important point;

- GTQ or PTQ to mark a good or potential test question;

- Arrows to show cause and effect relationships or to show association with other knowledge (e.g. This theory is completely similar (or different) from;

- Reflective comments to help you recall or comprehend;

- Reminders to yourself (e.g. search the internet on this;

3. Paraphrasing;

Paraphrasing involves putting learnt information into your own words. It is one of the most useful skills needed by students. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

A paraphrase is...

your own rendition of essential information and ideas, presented in a new form;

a more detailed restatement than a summary, which focuses concisely on a single key idea;

Basic Steps to Effective Paraphrasing

1. Reread the original passage until you understand its full meaning;

2. Write your paraphrase on paper;

3. Check your rendition with the original to make sure that your version accurately expresses all the essential information in a new form;

4. Summarising;

Summarising is essentially condensation of your learnt material put in your own words. It is also one of the most useful skills needed by students. This skills helps with all of the following: reading comprehension, monitoring reading and learning skills, textbook study, preparation for essay tests, note-taking/note-making, writing research papers, and recall of information.

The following steps will help you write good summaries:

- Survey the material you will have to summarise;

- Let your purpose guide you in determining the organisation & length;

- Read the material through once or twice for key ideas;

- Note how ideas are related to each other;

- Reread, looking for the key ideas of each paragraph;

- Write the opening statement that you think expresses the key idea;

- Write the ideas that support the key ideas;

- Avoid including details, examples, anecdotes or other material besides the key ideas;

- Do not repeat any information;

- Do not include your opinion;

- Use your own words;

- Remember: Your summary should read like a coherent, unified paragraph in its own right!

(Personal Notes:

To paraphrase and summarize successfully, keep two principles in mind as you read and record notes.

1. When reading materials, treat each passage as a discrete unit of thought to be assimilated into your own thoughts. Try to understand the passage as a whole, rather than pausing to write down ideas or phrases that seem, on first inspection, significant. Read purposefully, with a larger conceptual framework in clear view, and integrate each reading into that controlling purpose.

2. After reaching a clear understanding of the ideas contained in the text, summarize that information in your own words. Remember that you are taking notes, not copying down quotations. Your task is to extract, distill and compress essential content that will be useful in creating a paraphrase.

5. Outlining;

This is one of the popular note-taking and note-making formats.

Here are some basic outlining guidelines:

- Make a simple list of the key points you want to include on paper;

- Scrutinise the list to check for ideas that should be added;

- Determine the best order for the topics in the list;

- Put all ideas in a form that shows the proper subordination of ideas;

- Feel free to revise your outline any time you feel that it is not working;

- Always keep your overall topic in mind as you outline or revise your outline;

From my consulting/training work with kids and teens, I find that the most effective outlining method is the ‘Cornell Notes Method’, which I believed is developed by Prof. Walter Pauk of Cornell University.

With ‘Cornell Notes Method’, firstly, the page is divided into two vertical columns; one is one-third of the page wide (the Recall & Review Column), the other two-thirds (the Notes Column).

About 2 inches from the bottom of the page, you create one horizontal column. This is the Summary Column.

In the Recall & Review Column, you fill it with key words and phrases and with questions. The idea is that you complete this column after the note-taking exercise in the Notes Column.

The words and phrases you place here are meant to represent your selection of the key ideas of a reading or lecture. The questions you enter serve to help you clarify unclear ideas and to elaborate on the notes by connecting ideas together.

You complete your summary of the notes on the page in the Summary Column.

For more information about ‘Cornell Notes Method’, I recommend you to read Walter Pauk's ‘How to Study in College’ and/or‘Essential Study Strategies’.

6. Mapping;

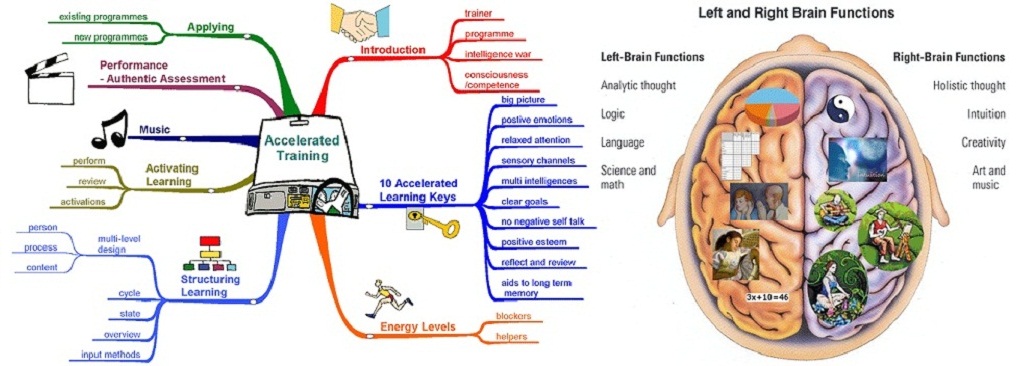

In addition to the ‘Cornell Notes Method’, you may wish to use a non-linear way of organising your notes, called ‘Mind Mapping’.

‘Mind Mapping’ is developed by Tony Buzan from UK. You can read about it from his book, ‘Using Both Sides of the Brain’.

His other book, ‘The MindMap Book’, is worth exploring as it has many colourful mindmap samples.

Mind maps are diagrammatic ways of organising key ideas from textbooks or lectures, which emphasise the inter-connection of concepts and illustrate the relative hierarchy of ideas from titles, to main concepts, to supporting details.

Because they are diagrammatic, they have the potential to capture a lot of information on a single page. They help to show the conceptual links between ideas and allows for additional material to be added without the need to crowd the page.

And, because they typically feature key words and phrases, they allow for the same kind of review that is facilitated by ‘Cornell Notes Method’.

In a mind map, the central topic is placed in the centre of the page, placed in a landscape format, and the key ideas related to it are placed on branches that directly connect to the central topic.

The details which support these key ideas are then directly linked to the key ideas (and thereby, indirectly to the central topic). There is room to add information on further key ideas and you can add colours or doodles to accent your work

Personal Notes:

If you simply don’t like mind-mapping, there is another simpler and easier method. Its called clustering, developed by Gabriele Rico, in her pioneering book, ‘Writing the Natural Way: Using Right Brain Techniques to Release Your Expressive Powers’.

There is another interesting diagramming method developed byNancy Marguiles. Its called ‘Mind-scaping’. You can read about it in her book, ‘Mapping Inner-Space’.

7. Recapitulation or Reconstruction;

Here you combine all your outlined or mapped notes into one large global outline or global mind-map, generally on a subject-by-subject basis.

In this global outline or global mind-map, you re-organise and consolidate all the key ideas and other important information from your myriad outlines or mind-maps, subject by subject, and transfer them onto one single sheet of large paper, each representing one subject.

This is the eventual piece of work which you will use to do your final review just before your final subject examination.

By recapitulating your notes and reconstructing the larger outline or mind-map, you are consolidating your whole years learning.

ADDITIONAL STRATEGY:

I like to introduce the follow natural vision improvement exercise:

- drink some water before you read; drink more water if you read extensively;

- do this Palming exercise: rub your palms against each other robustly till you feel the heat, and cup them against your eyes; and feel the heat massaging your eyes; your eyes can stay open if you want to; do it few times;

- occasionally, while standing under the sun, do this Sunningexercise: first, close your eyes, and face the sun; move your head gently as if you are writing the infinity symbol and in the direction of the sun; do this say for about 2 to 3 minutes; remember: don’t open your eyes!!!

- Do this Far/Near Focus exercise often: stand in an open space, where you can see some man-made or natural objects around you, both in the near as well as far distances; close one eye (say, right), stretch out your hand in front of you, clench it with the thumb facing the sky; look at your thumb and describe its features to yourself mentally; do it for a minute; then, pick a distant object; do you best to describe its features; do it for a minute; now, open your right eye and close your left eye; repeat the above instructions; when you have completed with either eye, now, repeat the instructions with both eyes open;

These simple but effective eye exercises are designed to relax your eye balls and also to keep them in peak condition.

[I had originally written this piece as an extended email response to a student in the United States, who had approached me for expert guidance to his reading problem in 2002. By chance, I have recently located this email.]