Learning To Learn

Spend Less Time Studying And Still Get Better Grades? Using My Effective Learning Techniques, You're Guaranteed Success!

One of the things that we expect you to pick up by osmosis, but almost never mention explicitly, is techniques for learning itself. After you leave university, you will be expected to be able to learn by yourself for the rest of your life. And an hour spent addressing the meta-issue of learning skills pays off in reduced time to actually learn.

A lot of work has been done over the past few decades about how people learn. This document suggests a wide range of techniques that may make your learning more effective. You may want to experiment with some of them to see if they work for you.

I recommend the work on accelerated learning by Colin Rose and Brian Tracy. You might also want to read J.J. Gibbs, "Dancing with your Books".

Principles

1. You can learn anything if you have a goal that requires it. This implies that you must connect what you are learning to your personal goals in a credible way. Trying to learn because of some second-order benefit (getting a credit or a credential) will seem very difficult.

2. Learning how to learn is the core skill. This is probably the one skill that was never explicitly mentioned in all the years that you've spent in school. But it's the one where there's the most reward for the smallest investment.

3. Anyone can learn faster by structuring the information. This is another one of those common trade-offs - getting right into it can feel satisfying, but taking some time to organise can increase effectiveness, even if it doesn't feel so satisfying in the short term.

4. Intelligence is not fixed. You probably know that the idea of a single monolithic thing called 'intelligence' is in disfavour right now (see Martin Gardner's work). There seems to be some evidence that what we might intuitively think of as intelligence (e.g. the ability to get things done cognitively) can be increased by several kinds of mental activity.

5. Learning more means earning more. Those who learn more, and do it continually over their lifetimes, do much better in whatever career they have chosen.

6. Knowledge and skills overcome obstacles. Improving both are survival skills no matter what your situation.

7. Everything to which you were paying attention, either consciously or unconsciously, will be remembered permanently. What seems to get lost is a way to access these memories. So effective learning requires you to be there, in the moment, and to make the things you learn memorable, i.e. easy to access. Anything that makes what you are learning different helps to make it memorable. So does the emotional content you associate with the material.

There are a number of stages to learning, each of which involves a number of aspects. Some version of this sequence is appropriate whenever you sit down to learn. The sequence also applies at higher levels: whole course, the whole of your degree, and even your whole life.

The right state of mind

There are six aspects to being in the right state of mind to learn. If you think about a situation where you seemed to soak up knowledge without any real effort, you will probably find that all of the aspects came into play. Imagine how nice it would be if everything you had to learn came so easily.

Here are the six aspects:

1. Find a personal reason to want to learn this material. This may be something that's already clear in your mind, but it may be something that you have to create. Creating a desire to learn something specific may require connecting the knowledge to your self-image; it may help to think in terms of missing skills that you would like to have; or you may need to connect the knowledge to your larger goals. However, if you don't have a good reason to learn, learning will not happen easily and may not happen at all. You can't be compelled to learn.

2. Having come up with your reasons for learning something, you need to translate these reasons into motivation. Asking questions like "what's in it for me?" may help. For most people, increasing the emotional content of the reason adds extra motivation. Try to visualise, hear, or feel some situation that will result from having learned the material.

3. Find a way to make the material relevant to you, right now. One way to do this is to ask, "what's most important about this material?" or "how can I use this material right away?".

4. Build anticipation about learning the material. Imagine what insights might come to you when you really understand the material. Imagine polishing off assignments or the final exam easily. Imagine being able to answer a technical question stunningly at a job interview. Whatever it takes, find a way to want to get started.

5. Have positive expectations: that you will find the material easy to understand, that it will be interesting, that it will be exciting, that it will be useful, that it will connect up to what you already know. Expectations are self-fulfilling prophecies - what you expect is what you get.

6. Have a calm mind. Learning seems to work much better if you're generally relaxed. Some things that might help:

o consciously relaxing, and playing music that helps you stay relaxed;

o deep breathing before you start, and frequently during your learning period;

o having an organised place to work so that you're not constantly distracted by other parts of your life;

o giving yourself rewards when you have completed some task effectively (don't make these time-based or else you'll become a time-server in your own life).

A variety of ways of input

Here is a list of ways you can use variety in getting new material:

- Play to your strengths in terms of how you process information. Some people tend to visualise, other process information auditorily, while others process it kinesthetically. (Try this quiz). Use whatever your dominant technique is when you try to get a handle on something new, when you see how things fit together, or when they sound right.

- Make a general outline of what you're learning.

- Ask "what will I be able to do differently because of learning this?".

- Browse through the material, looking at headings, pictures, tables etc.

- Ask "what do I already know about this?".

- Ask "what do I need to find out about?".

- Break the material into small chunks; or start anywhere.

- Ask yourself questions before or after looking at each chunk.

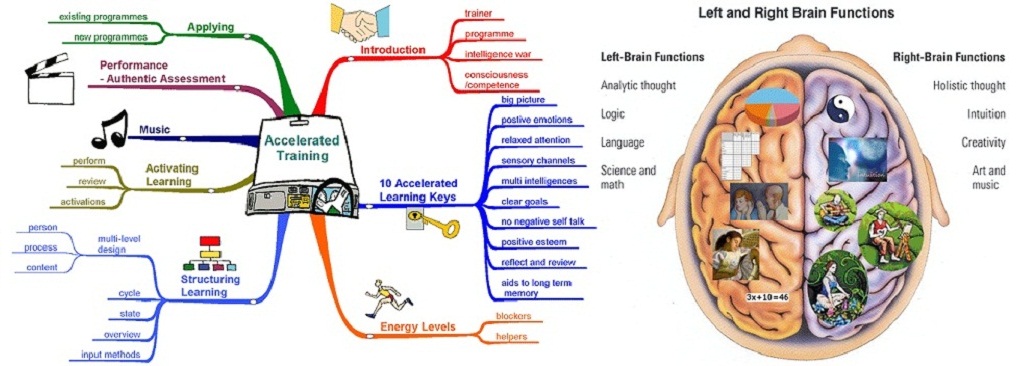

- Use mind maps.

- Tick off each section as you read it, or when you understand it. Get tactile.

- Highlight new information. (Using a highlighter can be useful, but highlighting often becomes a substitute for reading; instead find other, more varied ways of emphasising the important points.)

- Read the important points dramatically, or whisper them (we're used to thinking of whispered words as important!).

- Summarise the material out loud.

- Visualise the material internally.

- Walk around while reading or listening.

- Put key ideas on post-it notes and arrange them in different meaningful patterns on your desk, board, or wall.

- Make notes of your own thoughts, not of the content of what you are interacting with (i.e. don't copy from it, and don't paraphrase it - generate your own version).

- Go for a walk. Your brain seems to consolidate what you've been learning if you give it some peaceful "cooling down" time.

- Use the buddy system. Ask each other questions about what you've learned.

Exploring from different angles

Howard Gardner has suggested the existence of 7 intelligences, clusters of related abilities. Some of the ways in which you might be able to bring these into play is to look at the material in different ways that are related to them.

- Linguistic intelligence - describe the material out loud, or use question and answer format.

- Logical-mathematical intelligence - use a flowchart or diagram for the material.

- Spatial intelligence - make an image of the material.

- Musical intelligence - play background music as you learn.

- Interpersonal intelligence - teach someone else.

- Intrapersonal intelligence - ruminate on the material.

- Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence - use index cards sorted in different ways.

Another major issue is the chunk size that you naturally choose when exploring something new. If something seems hard to understand, maybe you need to `chunk up', that is move up one logical level. On the other hand, if you don't feel as if you really get it, then maybe you need to `chunk down' and move down one logical level. You may also find that you organise things into chunks of particular sizes, and that you feel overwhelmed by a topic that exceeds your normal chunk size, or swamped by one that is too small.

It's also a good idea to put the things you see into a framework, that is connect them to what you already know. It doesn't much matter if you build this framework top-down or bottom-up, but the existence of the structure reduces your feeling of `lostness' and also reduces the amount of explicit content you have to remember.

Memorising

Here are some ways that might help you memorise:

- Decide to remember.

- Take regular breaks.

- Review notes regularly: after an hour, after a day, after a week, after a month, after six months. (You'll need an organised way of making sure that this happens, but it is extremely effective.)

- Use multisensory memories, i.e. remember using as many representations as you can.

- Generate visual images that involve moving, interaction, and colour.

- Use the same background music to review as when you learned, and perhaps associate particular music with particular topics.

- Organise meaningfully using key words.

- Look briefly at a mind map, then put it away and try to recreate it. Repeat until you can reproduce it perfectly.

- Use flash cards with the key content on them.

- Use higher-order mind maps to connect individual mind maps together.

- Use mnemonics or acronyms.

- Review at bedtime.

- Number points.

- Overlearn, i.e. learn beyond the point at which you have complete recall.

- Compress the amount of material by chunking and using keywords.

Showing you know

Demonstrating to yourself that you really do understand and remember can increase your confidence that your learning is really working. Teaching someone else, or writing mock or practice assignments and tests, can be useful here.

Reviewing and reflecting on the process

After every learning session, review the process you followed. What worked, what didn't, what would you do differently next time. Do the same thing at the end of each week, after each assignment, and after each tests. Make notes of what you've learned about learning, and use them to improve your next learning session.